Renewable Energy as Military Strategy

John Ehrett

All too often, public discussions about the military, energy, and the environment devolve into caricature: consider the ubiquitous meme of a “military-industrial complex” devoted to oil extraction and profiteering above all else. Such binary thinking obscures the creative ways the military is responding to environmental and energy challenges, and downplays its unique leadership role in developing renewable energy solutions. The “Maintaining National Energy Security: The Role of Fossil Fuels in America’s Defense Strategy” panel at Yale’s 2017 New Directions in Environmental Law conference was a refreshing counterpoint to this shopworn “military-industrial” narrative, and outlined a number of creative paths forward for the American defense establishment.

Moderator Michael Oristaglio, executive director of the Yale Climate and Energy Institute, framed the conversation around two major topics: the role that fossil fuels play in U.S. military operations and defense strategy, which in turn raises questions of environmental impacts and human rights; and the military’s ongoing plan to move away from fossil fuel use for strategic reasons. In the event of energy supply disruptions, Oristaglio noted, a military overreliant on fossil fuels would find itself in a difficult strategic position.

These issues took center stage throughout the panel, as discussants explained the broad strategic benefits of adopting renewable energy sources. Dan Kenny, security and emergency management specialist for Newfield Exploration and veteran of the U.S. Coast Guard, stressed that renewable energy is the key to the military’s own goals of energy security. Simply put, the military doesn’t want to be exclusively dependent on one type of fuel; at present, disruptions in the military’s access to oil would hinder the military’s war-fighting capability. This risk becomes particularly important as the U.S. military allocates more resources to the Asian and Pacific region in order to balance an emerging China: longer distances between island resupply points force commanders to depend on increasingly attenuated supply chains. Kenny’s core theme underpinned much of the discussion that followed: for the military, the costs of renewable energy can be justified in terms of strategic, not just ecological, gains.

Robert Goldstein, director of the Center for the Rule of Law at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, explained the national security impacts of changing climate realities. Wholly apart from questions of climate change causation, Goldstein said, the Syrian crisis—which has swelled to involve over 11 million refugees—was undeniably exacerbated by a series of droughts. These droughts damaged food supplies and concentrated populations around cities, producing a powder-keg environment that erupted into civil war. Furthermore, rising sea levels are placing South Asian nations at serious risk, and could trigger a refugee crisis involving 150 million people. Such dynamics lead to the real potential for conflicts over scarce natural resources—conflicts the U.S. military has a strong interest in preventing. Accordingly, pursuing renewable energy doesn’t just benefit the military directly (by removing the need to depend on potentially unstable sources of fossil fuel), but also has the indirect benefit of mitigating global risk overall.

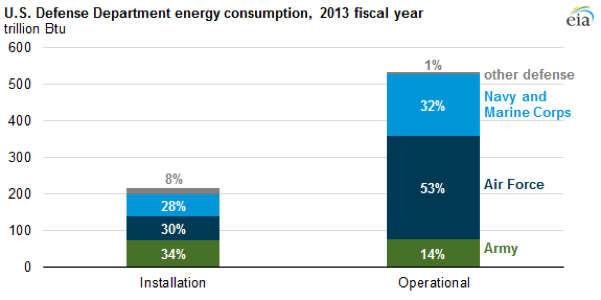

Moving into the realm of concrete particulars, Chris Smith, former Assistant Secretary for Fossil Energy at the U.S. Department of Energy, noted that the military will always be an enormous source of purchasing power, which means that it can accelerate shifts toward renewable energy because the military demands high  quantities of energy—enough to power roughly 2.7 million American homes. Currently, the Department of Defense has made it a priority to “meet at least 20% of energy demand with renewable energy resources by fiscal year 2020.”

quantities of energy—enough to power roughly 2.7 million American homes. Currently, the Department of Defense has made it a priority to “meet at least 20% of energy demand with renewable energy resources by fiscal year 2020.”

Smith went on to describe the difficulty of convincing developing nations to make energy policy decisions based on global environmental goals: after all, countries combating extreme poverty are often motivated by immediate concerns of human welfare. One way to bridge this gap, Smith suggested, might involve explaining the most efficient ways to improve access to electricity and other basic services—ways that frequently include use of renewable energy sources. Framing issues in the language of “stability” rather than “climate” is one promising solution: it aligns with local lawmakers’ interest in building a workable governance system, while simultaneously working toward common environmental goals.

Interestingly, despite their shared support for expanding the military’s use of renewable energy, all four panelists agreed that military leaders ought not involve themselves in political infighting over climate change. This reticence is grounded, Goldstein stated, in the military’s structural commitment to civilian leadership: whatever administrative mandates policymakers set, military leaders will work extremely hard to achieve them.

Given this institutional reality, the panelists’ collective emphasis on national security and war-fighting competence represents a unique, and as yet underexplored, opportunity for civilian leaders to advance the conversation on environmental and energy policy. By stressing the need for the military to rely on multiple energy sources (so that disruptions to one source won’t place national security at risk), they make a deeply pragmatic case for developing renewable energy systems. This pragmatic approach has great potential: at a time of rising civic populism, where globally-minded arguments are unlikely to find much societal traction, framing the renewable energy question in terms of national security allows policymakers to reach citizens across the political spectrum.

While significant public support could likely be marshaled for a broader-based military energy strategy, actually translating this framework into a cohesive scheme would likely be much more difficult. Civilian legislative efforts to promote the military’s renewable energy goals would undoubtedly face pushback from entrenched political interests and powerful lobby groups: industry groups devoted almost $120 million to lobbying in 2016 alone. This barrier, however, is not insurmountable: according to Jeremy S. Scholtes, writing in the Energy Law Journal, “opportunity and financial gain will motivate the private sector to think far outside the box.” Partnerships with private industry—and the promise of further government contracts for successful innovators—can be powerful accelerators of a shift toward renewable energy.

The stakes involved in this debate transcend partisan lines. Initial startup costs aside, expanded military use of renewable energy offers the potential to both enhance military effectiveness and reduce the environmental impact of fossil fuel overconsumption. Given these advantages, civilian decision-makers should not overlook the military’s potential to play a key leadership role in diversifying America’s energy supplies.

In the years and decades to come, military leaders will routinely find themselves on the front lines of confronting environmental change. Policymakers should take their recommendations seriously.